Service Design : "KID MODE"

My Role: User Researcher, User Interviews, Cardboard Prototyping, Usability Testing & Evaluation

Tools: Lo-Fidelity Prototypes - Pen, Paper, Colored Pencils, Tape, Cardboard

Timeline: 2 weeks

Keywords: Contextual Inquiries, Affinity Diagram, Observations, Embodied Knowledge, Usability Testing, Group Project, School Project

OVERVIEW

Objective: Enhance the shopping experience of grocery shoppers by maximizing positive interactions, while considering tradeoffs between patron convenience and potentially reduced sales, as well as the ways in which technology may disrupt current monetization strategies.

Approach: Our final proposed product is an enhanced self-checkout feature: a “Kid Mode” feature which creates a “scene” on the screen as items are scanned, along with a recipe involving those items. In addition to engaging adults and children, our research found that early engagement in this manner often leads to healthy, lifelong habits.

UX PROCESS

INITIAL RESEARCH

Early research and investigation of literature presented several opportunities to explore cooperation and constructive positions in family co-shopping. As a group, we discussed how this challenged our own ideas about the role children play in the grocery shopping experience and wanted to learn more. In this early phase, we limited our scope to Pay-Less stores in order to constrain variables such as layout, clientele, etc.

This research was supported through our first round of interviews as well. When asked about grocery shopping as a child, one interviewee, a self-described grocery store enthusiast, recalled the following:

“As a small child, I used to go grocery shopping with my mom...we’d go every Saturday or Sunday [when I was really little]. We would sit in the kitchen and open the pantries. I mean, she was a mom with three kids, plus a husband, so it was a much more expansive grocery list. And then we’d make the list [together].”

Another interviewee, an avid homecook, told us the following:

“I grew up in a house where my mom would cook and...listen to Dean Martin...and everybody would come into the kitchen and talk and listen to music. It just became this thing that I enjoy. So at the end of the workday, I can't wait to just....turn on some music and...cook”

In this situation, cooking was not just a means to an end. It was an opportunity for familial bonding. We kept these anecdotes in mind during our first contextual inquiry, a trip to Pay-Less at 8:30 AM, during which we observed several parents with children who seemed more like passive companions instead of active co-shoppers. We began ideating on how to involve children during the shopping experience.

IDEATION & REFINEMENT

We attempted to address our findings from research through a round of sketching. Our initial sketches explored different ideas that would potentially engage children during the grocery shopping experience. These ideas included

(1) a parent-child linked cart system

(2) a modified app coupled with traditional in-store print materials

(3) a racetrack game that would highlight the child’s next “stop” for a predetermined list of ingredients.

|  |  |

|---|

While all our sketches addressed a variety of approaches we determined to narrow our scope further. Around this point, we determined it would be helpful to conduct a few more interviews regarding experiences different shoppers had as a family. Our interviewees included people with strong family grocery shopping memories, as well as people whose parents neglected the family shopping experience.

We took notes from the interviews and organized them into an affinity diagram to help identify common perspectives. While our initial diagram didn’t offer much insight directly, reorganizing the affinities by emotion presented strong opportunities. This was most clear when it came to feelings of nostalgia as feen in the figure below:

We identified the relationships from our emotional affinity diagram as an area of opportunity for increased engagement amongst parents and children. To look further into this, we consulted more literature; this time focusing on the effects of shopping as a family.

At this point, we refined our focus to address three to six year-old children and the co-shopping with parents at Pay-Less stores.

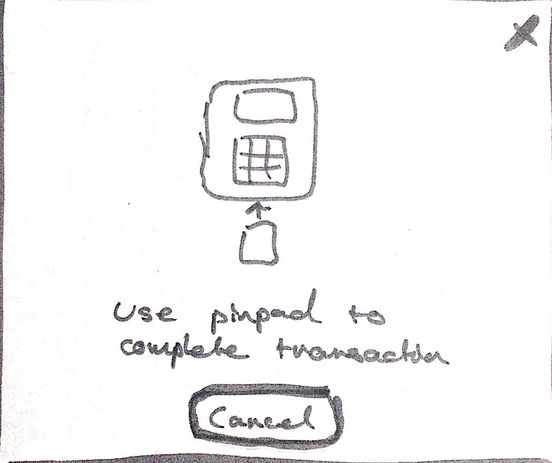

Having a clear and focused audience in mind, we decided to meet them where they were (again!) by conducting a follow-up contextual inquiry. Through observations of three various families, our biggest takeaway from this second session was that children were completely unengaged during the self-checkout process (the preferred method of checkout for the families we observed). Therefore, we decided to focus on this final part of the grocery experience.

This discovery led us to another round of sketches and finally, the following prototype.

PROTOTYPE

When it came to prototyping methods, we truly had to put ourselves in children’s shoes. We believed working with tangible objects, such as an egg container, as well as creating sound effects when buttons were pressed, would be necessary in order to engage with children when testing our prototype. Our goal from generating this prototype was to see if children will understand how to use it (through a usability test), if they enjoy building a scene and if they are engaged with the prototype (evaluated through a post-session interview).

This prototype replicates what the parents and the child will see when first coming to the self-checkout. From here the child (or adult) can press “Kid Mode” in order to engage in the interactive experience of scanning items, creating a scene, and ultimately, having a recipe card printed off as a means of encouraging them to go home and cook with their parents.

TESTING & EVALUATION

We tested Kid Mode through two usability tests and evaluated it through a post-session interview to discuss the children’s experience as well as the parent’s. Our testers included a five-year-old and a three-year-old. We made the usability test as interactive and engaging as possible while evaluating if they could use it with minimal adult guidance. As the children scanned items, we made beeping sounds, to simulate a scan, as well as “boop” sounds when items would “appear” (taped to the screen scene). Finally, we made printing sounds when the prototype printed the receipt and recipe card. The youngest user was so engaged after the first item and made the sound effects himself.

Following our usability test, we evaluated the experience with a post-session interview. While most questions were met with one word answers or nods, we learned more through our observation of the children engaging with the prototype. There were moments of joy appearing on their faces as items “appeared” on the screen and the child was in complete control of which items to scan next. Furthermore, both users were focused on what was happening and the prototype was successful in holding their attention.

Finally, we discussed Kid Mode with the parent of the children who said the following:

“I would love this if this was at a grocery store! While I do let my kids scan some items, I love the idea of taking home a recipe card that we can cook together when we get home.”

Furthermore, when it came to the actual test, the parent let her child have complete control with little guidance. We believe this level of trust and cooperation led to many moments of delight from the tester throughout the process.

CONCLUSION

We had set out to change the way families experience grocery shopping. From our research, testing, and analysis, we believe our solution encourages stronger engagements between parents and children that extend past the grocery shopping trip. Although obvious limitations still need to be addressed within our solution, our proposed design integrates seamlessly in the current environment without degrading the shopping experience for other shoppers. Through each stage of the project’s development, we were driven with purpose﹣ from discovering an opportunity in the current setting of grocery shopping to effectively developing a strategy for promoting interactions currently lacking in the space.

Based on our research, the proposed design has the potential to create long term skills that lead to improved proficiency in shopping and cooking when children grow up and become independent. This is outside the scope of our project, unfortunately, but we are curious to see the extent of the impact if the design is implemented.